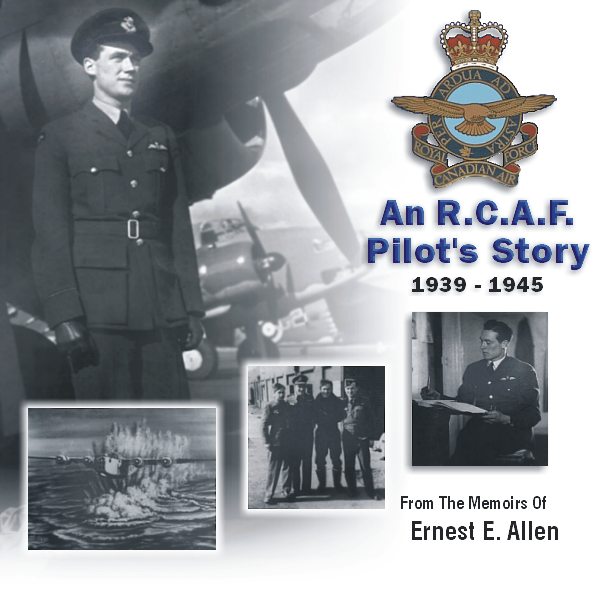

Part 2 – Called To Duty

Per Ardua Ad Astra

(Through Struggle To The Stars)

Pilot Training | Called To Duty | Liberators | End of Tour | Epilogue

On December 9, we pilots were all called into the Ferry Command office at Dorval and advised that the Americans had cut off the supply of aircraft to the R.A.F. There were four Hudsons already at Dorval. An instructor was to take one, and the other three would be taken by three of our crews and the rest of us would be shipped out to Halifax and go by boat. The decision as to which three pilots would take an airplane was made by drawing straws. I got a straw that meant I was to go to Halifax and I was not sorry, as flying the Atlantic was a big deal in 1941, and I was not at all confident that I would be successful.

After a couple of nights in Montreal, we were put on the train to Halifax, a ghastly place in December 1941 and on December 24, we went on board an old ship, the name of which has been long forgotten, but I do remember that it had come across from North Africa with the hold loaded with Italian prisoners of war. They were being shipped to England to work on farms.

Our ship was travelling in convoy, very slow, and detouring a lot because of U-boats. The trip took us two weeks and we made port in Glasgow in northern Scotland. On the way over, we aircrew were required to stand watch – four hours on and four off. Off watch we slept a lot and learned to play bridge.

From Glasgow we were entrained for Bournemouth on the south coast. The English were very concerned about the risk of air attack and it made the trip more exciting for us. Bournemouth was a holding unit for aircrew to wait in until someone decided where to send us next. We were billeted in hotels with no heat. We had bed sheets but the humidity was so high we could wring water out of them, and we were cold all the time. I sent a telegram home to send me some long underwear but by the time it arrived I was acclimatized and didn’t need it.

My brother Edsell had enlisted in the 48th Highlanders in October 1939 and had been shipped to England in February 1940. At the time I arrived in Bournemouth, I was told that the 48th Highlanders were in Littlehampton, just up the coast a bit from Bournemouth, so I took a bus up to Littlehampton and was successful in locating “D” Company of the 48th, Edsell’s company. He was confined to barracks as a punishment for being three days late in getting back from leave, but he was allowed out during my visit. It was great to see him again and we had a lot of news to exchange. We must both have been well trained, or was it brainwashed. He was damned glad he wasn’t in the Air Force and I was equally glad I was not in the Army.

His unit had been sent into France in the spring of 1940, just when the Germans were doing their break-out into northern France. They didn’t see combat then, as the generals turned them around and sent them back to England through the port of Brest. This was at the time of Dunkirk and there was great apprehension that Allied troops would get trapped in France. Leo Cassaday, a chap I had gone through school with was also in “D” Company, and I had a good visit with him as well Leo was a survivor and the next time I saw him was in the 1950’s. He was personnel manager for A & P when I started to build A & P stores and was in and out of their main office in Toronto, a lot. It was good to see him again, but he would never talk about the combat experiences of the 48th in Italy, which was where Edsell was killed in the Casino campaign.

After about a month in Bournemouth, a bunch of us from Debert were shipped up to an overflow depot in Hastings remember Harold of Hastings from your history. It was here that we got together again with the three crews from our group who had flown across the Atlantic. They had had some exciting experiences on the crossing, but made it, whereas the instructor who had taken the fourth Hudson had disappeared in mid-Atlantic and was never heard of again. We began to think maybe our flying training wasn’t too bad after all.

We were slowly going out of our minds in Hastings, four of us pilots were billeted in a rooming house, and we were not really suffering but we were all impatient to get back to a flying station and get on the war.

|

|

About the middle of February we were posted to a Coastal Command operational training unit at Thornaby-on-Tees in Yorkshire. It was further training on Hudsons. Besides the more specialized training on the aircraft, crew training – bombing and gunnery practice – there was a change for the pilots in just keeping track of our position – especially in relation to Thornaby Airdrome. In Debert, just being able to see road and railway intersections gave us positive positions, but flying around Thornaby there were literally dozens of both road and rail intersections. It was much more difficult to know exactly where we were. Visibility was often reduced badly by smog, but with experience, we learned to cope.

They had not yet briefed us as to what to do in the event of German air attacks when we started night flying. That first night we were up night flying a bunch of German aircraft came into the area and of course, the runway lights were immediately turned off. We had no voice radio so we had to make our own decisions as to what to do. In my own case it had only just gone dark and I could see the contrast between the paved runways and the grass alongside, so I elected to go in and land. We made a “safe” landing, but when the tail came down, I found I had nothing to “keep straight” on. We ground looped but the only damage was a broken tail wheel lock. It was considered that the decision to land was a good one, but the training staff caught hell because they had sent us night flying without a briefing as to what to do in the event enemy intruders came into the area. Had we had the briefing, it would have been to turn off our navigation lights and go and circle a designated flashing beacon – each aircraft at a designated altitude!

It was here at Thornaby that pilots, navigators and wireless operator-air gunners sorted themselves out as to who would be in what crew. The general consensus was that the pilots would pick their crewmembers. It didn’t always work out that way. In my case it didn’t. While I dithered about who to ask to join my crew, AI Henry WOP/AG, Lloyd Woods WOP/AG and Don McLean, navigator, all three sergeants, had decided they wanted to be in the same crew. AI Henry, their spokesman, said the three of them had decided they wanted me as their pilot. I asked why they thought they wanted me. AI said they had good reports about me and they thought I was young enough to do things their way. As I looked them over – they were an intimidating bunch – and finally said fine, let’s give it a try. I figured it would be much better to teach them to do things my way and that they should remember that I was supposed to be the Captain. I calculated that when I got them in the air it wouldn’t be too hard to get things my own way. In any event there were no serious problems.

It was contemplated that when we finished our training at Thornaby, we would be posted to a Hudson squadron on the East Coast of England where our main job would be to do as much damage as possible to the German convoys along the Dutch coast.

It was stressed to us that, in patrolling along the Dutch coast, we would have to fly very low to stay below the German radar as they could not vector the German fighters on to us, to “splash” us. So, necessarily, most of our flying was at very low altitude over the water. I found that if I flew at about twenty feet, the crew were intimidated enough to give me no trouble. We were soon a happy and reasonably efficient crew and I was accepted as the Captain. One of the basic problems was that they were all seven or eight years older than I was, as I had not yet reached twenty years of age.

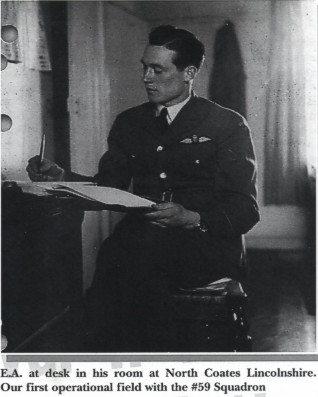

About the middle of March (1942) our crew and Roy Neilsons crew were posted to #59 Squadron on North Coates, Lincolnshire. Jack Gordon and Cam Barnett and their crews were posted to #53 Squadron, also at North Coates. The four of us had been together since our posting to Charlottetown on July I, 1941.

A bit of background on #59 Squadron is appropriate here. #59 Squadron had been formed during the 1914-1918 war and served on the western front in France. A movie of this was done with Errol Flynn and David Niven and still is a much-liked movie for old pilots. The squadron crest was a broken wheel about thirty inches in diameter. Sometime during that conflict, the squadron was given credit for knocking out a German artillery gun that had been causing a lot of trouble for Allied ground troops, and when our troops advanced they took the broken wheel off the gun and presented it to #59 Squadron in appreciation for their help. That same “broken wheel” was always prominently displayed in front of #59 headquarters and was still there when I left the squadron in November 1943.

In late 1941, #59 Squadron had been equipped with “Blenheim” bombers, until one day the whole squadron was sent over to The Dutch coast to attack a German convoy. NOT ONE AIRCRAFT SURVIVED TO COME BACK

The decision was then made to rebuild the squadron with HUDSONS and they were getting well along with this when Roy and I and our crews arrived. Some operations were day flights and some night flights.

The squadron was organized into two “flight”, “A” & “B”. Roy was posted to “B” flight and I was assigned to “A” flight. There was not much talk about retirement on this squadron.

My crew had just been declared fit for operations, when all flight crews were sent on detachment to Thorney Island, Coastal Command station just east of Portsmouth on the south coast. The story was that some more German ships were expected to try a run from Brest, through the English Channel and up to the Baltic Sea. My crew did not do an operational trip from Thorny. Only one crew did, and after a week we all flew back up to North Coates, toto find that “B” flight aircraft had all gone on a daylight ‘Op’ the day before to the Dutch coast – eight aircraft including the commanding officer. Roy Neilson’s crew was the only one to come back. His aircraft was badly shot up beyond repair, but none of the crew was hurt. The convoy was defended by both flak ships and land based fighters, which were based very close to the convoy route.

My crew finally got our first ‘ops’ trip a few days later, somewhere around the middle of April, a night patrol along the Dutch coast. It was a ‘no moon’ night. Lloyd Woods had booked off sick and as a replacement for him we had a Newfoundlander in the tail turret. We had been on patrol for only about ten minutes when the tailgunner reported a night fighter manoeuvring on us, and the Newfie called out for evasive action repeatedly. It was dark enough that we could not see the water from the cockpit and we had to rely on our altimeter as to our height above the water. We had no radio altimeters so there was always some uncertainty about our height above the water. I had to hope that if we stayed low enough the fighter night miscalculate and hit the drink while trying to get lined up on our trail.

Any sane pilot will tell you that taking violent evasive action on instruments in pitch darkness below three hundred feet is not an insurable occupation. Finally Don McLean reported from the nose compartment (the navigators workspace) that on the last manoeuvre, he had seen the water and that we had been down in a trough between wave tops. This information resulted in a backward pressure on the control column and a decision to try to ignore the evasive actions requested by the tailgunner. In summary, we did not get shot down. We didn’t fly into the water. We didn’t see any German ships. We did stay on patrol until the first light as we were supposed to. We did get back to base and I did change my underpants when we got back. And I did request that that Newfie gunner not be crewed with me again. So ended our first ops trip.

I found out later that the number of crews on Dutch coast patrols who failed to return from their first patrol in early 1942 was greater than fifty percent.

After three more night Dutch coast patrols, all uneventful, AI Henry, Don McLean, Lloyd Woods and I were having a strategy session in the local pub one night and I mentioned to Don that I had been steering a course from North Coates to the patrol area of one degree less than the course he was giving me to steer, so as to avid the risk of getting behind the Friesian Islands. At that point Don confessed that he had been deducting one degree from the calculated course before he gave it to me. By the time we had put away another two beers, we had determined that as a result of the combined two degree error we had been patrolling well outside the usual track of the Dutch coast convoys and we decided that in the interest of winning the war, from now on we would steer the correct calculated course.

So, on the next trip, we ended up inside the Friesian Islands and stirred up an undesirable reaction from the anti-aircraft” A A” guns located there for the “benefit” of Bomber Command, who often went in and out of Germany on this route. After going through a particularly bright nest of flack, I found Don had had dumped our bombs because he convinced himself that after going through that much flak, we would have to ditch in the North Sea. What could I say!!

We were on standby for shipping attacks for at least three nights for each night that we actually flew a trip. Crews kept failing to return. We lost another Wing Commander C.O., who failed to return from a trip. There got to be more crews on the squadron that we did not know, than what we did know, and it would be appropriate to say that morale fell to a new low.

Our third commanding officer – third that is since I had joined the squadron – a W/C Bartlett, got quoted as saying some negative things about Canadian aircrews in a pub one night, and by noon the next day, this information was all over the squadron. Roy Neilson and I had the only completely Canadian crews on the squadron, but there were a lot of other navigators and W/Op A/G’s. Roy and I had a discussion about this and decided we should request a posting to a Canadian squadron. We got paraded in front of Bartlett and made the request. He asked us to leave the request with him.

About a year later, Bartlett was sent to the O.T.U. at Nassau in the Bahamas, as Chief Instructor. It was an O.T.U. whose main purpose was to train Liberator crews to feed the R.A.F. Coastal Command in England. Roy and I ended up in Nassau in late 1943 where we found Bartlett had specifically requested that we be posted there on completion of our operational tour. To this day, I still think Bartlett was the best C.O. I ever had.

Back to North Coates. In the spring and summer of 1942, the Hudson squadrons were not sinking many ships on the Dutch coast. The Germans had built up a system of escorting flack ships for the convoys and this was a very formidable force. In June, daylight attacks for Hudson squadrons were forbidden as a matter of policy, for Dutch coast patrols and attacks.

A lot of pressure was being put on at Group level to improve our anti-shipping results and to reduce our casualties. The last tactic they came up with was to lay on attacks on Dutch coast convoys on the basis that each Hudson equipped with radar would take out three or four Hampden torpedo bombers at night. The Hudsons’ radar would pick up the German convoy and at an appropriate time, and after giving a visual signal to the Hampden, the Hudson would climb to 5,000 feet and drop flares over the convoy, illuminating it for the Hampdens to be able to aim and drop their torpedoes from their usual very low altitude. We had #415 Hampden squadron (Canadian) at North Coates with us at that time and my crew was chosen for the Hudson in the first of three proposed attacks, and one night in July we set off with three Hampdens following us. (There were supposed to be four, but one of them got ‘engine trouble’ just before take-off and stayed on the ground.)

A word is needed about this radar that we had on our Hudson, compared to what we got later on Liberators – it was very elementary stuff. It ‘searches’ the area in front of the aircraft. Flying over the water, if there was nothing there the radar operator – in this cases AI Henry – would see on the radar screen what was called ‘sea-return’, and if this ‘sea return’ was normal the set was presumed to be serviceable. The Hampdens were able to follow us because from the rear of the Hudson, our exhaust stacks were very visible.

We set our from North Coates heading for the Dutch coast to the position of a convoy that had already been reported by a patrol aircraft. We flew at three to four hundred feet. As usual we got a bit more tense as we got close to the patrol area. Suddenly, with no warning from our radar, a mass of anti-aircraft ‘tracer’ erupted all around us, our aircraft being hit repeatedly. It was obvious – we had flown over a well-defended convoy. We broke away to the north. Our tailgunner George Fleiger, (Lloyd Woods was off sick again), reported seeing the Hampdens badly hit by the flack. He was sure that two of them, possible three, had been ‘splashed’. Our aircraft was still flyable, but with the Hampdens knocked down and our radar still unable to pick up the ships, there was no point in climbing to 5,000 feet and dropping the flares, so we headed for home.

On pulling away from the flak, as usual we did an intercom check to see if all of the crew was still with us. We got no response from the tail turret, George Fleiger. Fearing the worst, I sent AI Henry back to check it out. When we finally got the story sorted out from both Fleiger and Henry, it went like this: Fleiger said that when the flak first started coming up, it looked like every gun in the convoy was firing personally at him, so he ducked his head down behind the bullet-proofing – the bottom half of the turret. In his keenness to get completely protected, he got his head down too far and got his headphones tangled up in his parachute harness and lost track of his microphone. This was how he was when AI Henry came to the rescue. Between them they got it sorted out – after AI tried to convince George that he should swing the turret around and jump out, because obviously some of those German gunners wanted to get to know him better. I guess they were just having fun!

As usual, on returning from a ‘night ops’ trip, we landed at our satellite field, “Donna Nook”, a few miles south of North Coates – a grass field. It was one of the best touchdowns I ever made. Fleiger called out on the intercom “Good show Ernie!” Then as we slowed down, the starboard undercarriage gave way. I held the wing up as long as possible with the aileron, but as we slowed further the wing went down and we ended up sliding out of control and finally came to a stop. As the Hudson had a bad reputation for burning in such an ‘arrival’, we lost no time in evacuating the aircraft and found we were on the edge of a deep drainage ditch at the end of the field. Another twenty feet and we would have been into the ditch, probably with the wing broken and with the gasoline in the wing tank, a gasoline explosion would have been the inevitable result.

Needless to say, during our return to the English coast there had been considerable discussion as to “why didn’t our radar pick up the convoy?” AI Henry had been on the set the whole time and he insisted that by every means he could tell, the set was working lots of ‘ sea return’, but no sign of any ‘ship return’, before the flack indicated we were over the convoy.

Within a few minutes of our coming to a stop, a vehicle arrived and among its people was our squadron Radar Officer, a Canadian. I gave him a brief verbal report re our radar not working – as a result of which the Hampdens had all been shot down – there would be hell to pay. That he had better get the set tested and be prepared to give a report on it at our debriefing in the Ops room. We were taken there by the vehicle, where the Group Operations Officer as well as all the other usual intelligence people were in attendance.

Al and I were locked up in a room by ourselves to speculate as to “what happens now”, including the possibility of being “shot at dawn”. We were able to joke about it, but there wasn’t much humour.

After several hours Al and I were taken back to the Ops room and brought up to date. Al and I were cleared of all responsibility for the radar problem. The Radar Officer had reported on the radar set – that a tube was blown in the set, which had the effect that it would pick up a normal sea return but could not pick up a ship return. Also, we learned that one of the Hampdens had made it back. It crashed landed on the beach and the crew walked out through a minefield on the beach, which they were not aware, was there. Their report substantiated ours as to the events at the convoy. Sleep did not come easily that night.

The tactic of combining the Hudson and Hampden attacks was never tried again. I think that was the last Dutch coast trip our crew made. Shortly after that, all ‘A’ flight aircraft were transferred ‘temporary duty’ to Thorney Island again.

On the night of, I think, August 20, 1942, a number of our crews were briefed to do a patrol off the French coast – from Dieppe to a point about seventy miles to the west – to report any shipping in a designated area. We were not told about our own forces – mostly Canadian – on the way to attack Dieppe. Our crew was assigned to the time period from two hours before dawn to ‘first light’. We patrolled just a few miles off the French coast and could see the coast all the time we were on patrol, at three hundred feet to avoid shore radar picking us up. As daylight started, we became very nervous about being there. We hadn’t seen any ship at all. We were pleased to head for home when we had a consensus that it was ‘first light’. There were a number of German fighter fields in that area.

Almost half way home, we saw away up above us a flight of about eight twin engine Boston Bombers headed for France. As we watched we saw a ‘vapour trail’ approaching the Boston flight from the rear of their formation. Then, a puff of smoke replaced one of the Bostons and we realized that one of the Bostons had just been shot down. We decided that we would be better off down in the layer of cloud below us and proceeded to do that the rest of the way to Thorney Island.

After debriefing, we went to bed until lunchtime. After lunch, we were walking across the parking lot when a FW190 came diving out of the cloud, firing at us in the middle of the parking lot. We all ‘hit the deck’, as bullets tore up the pavement all around us, but no one was hit. We thought that trying to kill us on the parking lot was carrying the war ‘a little too far’. After returning to the bar to get something for our nerves, we carried on over to our flight office. The activity that day of course, was the widely reported Dieppe raid by mostly Canadian forces.

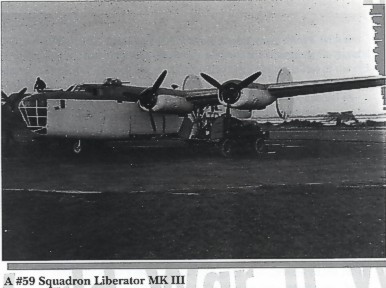

A few days later we returned to North Coates, where it was announced that 59 Squadron was now taken off operations on Hudsons. We were to move to Thorney Island and convert to the B-24 Liberators and join in the anti-U-Boat war in the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic. All aircrew enthusiastically received this news. It was like being born again. Attacking German shipping on the Dutch coast in Hudsons had no future in it, whereas the prevailing view was that with this changeover to Liberators, most of us would survive the war.

Apparently at a recent meeting between Churchill and Roosevelt, the U-Boat war was given top priority in the allocation of aircraft and the Liberator was judged to be the best aircraft available for the long-range patrols in the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic.

Was it luck that 59 Squadron was one of the squadrons chosen to convert to Liberators, or was it that in Wing Commander Bartlett we had a top rated C.O., and someone in the right place figured we had a lot of competent aircrew as well.

This contemplated move to Liberators changed my personal outlook as well. Early in the summer I had met an English girl, Doreen Hydes, that I was very much attracted to but as long as I was flying Hudsons on Dutch coast ‘work’, neither one of us saw much future. Now we both saw some future in looking at getting married. First I had to satisfactorily complete my training as a Liberator Captain. The squadron was moved to Thorney Island as soon as Liberator aircraft became available.

The squadron changeover from Hudsons to Liberators made for a lot of decision making from the C.O. on down. One idea talked of but discarded was the every captain should have the minimum rank of Squadron Leader. This idea was shot down on the fact that lots of Lancaster captains were sergeant pilots. There were many other reasons as well.

We also had a great deal of discussion about navigators being captain of aircraft. In 59 Squadron we probably had the most qualified bunch of navigators in the Air Force, and there was a great deal of friendly rivalry between the navigators’ union and the pilots’ on this captain question. It eventually happened on #59 Squadron in September 1943, when a second tour crew came in, and a navigator, S/Ldr, John Curtiss became his crew’s Captain. I cant recall ever meeting him on the squadron.

After I left #59, he became squadron C.O. and eventually served a term as Marshall of the Royal Air Force. I met him long after the war in Inglewood where we had made our home in 1967. Our next door neighbours in Inglewood were John and Barney Higham. John was a T.C.A. captain and an old Bomber Command pilot. Barney had been a stewardess on T. C.A. and before that, a nurse. John Curtiss had married a nursing friend of Barney. In the early 1970’s, Curtiss was a British Military Attaché in Washington, and met John Higham on a T.C.A. flight on which Higham was the Captain. In discussion, they found that their wives were old buddies, and Curtiss ended up visiting the Highams in Inglewood. Higham brought Curtiss over to meet Doreen and me at our house. As he was leaving, Curtiss noticed the #59 Squadron crest hanging in our family room. He turned on me and said, “What the hell are you doing with a #59 Squadron crest?” I started to explain that I had been a pilot in 59 Squadron in 1942 and 1943. This ended up in our having several more drinks, with the discovery that we had both been on the squadron at the same time for several months in late 1943 and never met. During that time I was the last of the old North Coates pilots left on the squadron and somehow – I think I was going through some kind of ‘battle fatigue’ or depression – I never got around to socializing with the replacement crews and had never met Curtiss.

When I met Curtiss in Inglewood, I realized he was the second “Marshall of the Royal Air Force” that I had met. The first was a chap by the name of Slessor who was C in C of Coastal Command in May of 1943, when he conducted an inquiry as to why 59 Squadron had lost three out of four Liberators on a convoy escort on May 7, 1943, my aircraft being the only one of the four to get back on the ground in one piece. But more details of that later.

The squadron conversion to Liberators was done at Thorney Island in September 1943. This was on the Mark III Liberator and initially had no radar. The crew was two pilots, one navigator and four wireless operator-air gunners who rotated between the wireless set, top turret gunner, beam gunner and tail turret. For this long range Liberator, the navigator was considered the most valued crewmember, as most flights were likely to be long range over the Atlantic. The pilots were going to be very dependent on the accuracy of the navigator to get us to our patrol area and home again.

I had concerns about keeping Don McLean as navigator. Five months as my navigator on Hudsons on low level work had given Don a bit of a twitch and I was concerned about his drinking. It was a touchy thing to deal with, especially as Don and Al were good buddies. George LaForme had been navigator for Jack Osborne, an Australian pilot on the squadron. He had gone on rest, so George was looking for a crew. He and I had become good friends and he and George Fleiger, a W/Op. air gunner, who had filled in. in our Hudson crew when Lloyd Woods was off sick. Fleiger was giving me a good build-up as a pilot and LaForme and I ended up discussing the idea of his becoming navigator of our crew. I had to tell Don McLean I was making a change. I felt like a real shit about this and for awhile it looked as though Al Henry would leave the crew as a protest, but with considerable input from LaForme and Fleiger, we finally convinced Al that it was for the good of the crew and Al elected to stay with us. This was a great relief to me as I considered he was by far the best W /Op in the squadron. Don McLean ended up a few weeks later as navigator with a second tour pilot, Flt. Lt. Heron, an Englishman. When he converted to the Fortress, Heron overshot on landing at Chivenor and the aircraft was a write-off. Two W/OP AG’s were killed but Don survived with a few aches and pains.

Lloyd Woods was by now back on the fit list, and we picked up another Canadian W/Op by the name of ‘Bart’ Barton. So the crew was sorted out except for our second pilot. Our flight commander S/L Evans came to me and asked that I consider a young English sergeant by the name of Tommy Thomas. His story was that Tommy had been rejected by several crews. He was a ‘discipline’ problem and as Evans said, since my crew was all Canadian, Tommy might fit in. (All Canadian aircrew were considered by the RAF to be discipline problems.) After several sessions with the rest of the crew, there seemed to be a consensus that if I had troubles with Tommy, AI Henry would straighten him out.

It worked out well. Tommy had an effervescent personality and he made life a little less ‘dour’ in the crew. He never missed a trip and in July, after AI Henry was wounded and Lloyd Woods and George Fleiger went back to Canada – Barton, who had problems with the other W/Ops left to join a Canadian squadron and Tommy went on a Captain’s course. He came back to #59 Squadron and before he finished his tour, he had sunk a U-boat in the North Atlantic and was awarded the D.F.C. We Canadians had trained him well!

My logbook, which I had left for safekeeping when I was home on leave in December 1943, disappeared and I have been fortunate to have ‘borrowed’ George LaForme’s logbook. From a copy of that portion covering the period George and I flew together, my memory of that time has been greatly supplemented. I have difficulty accepting the total times of some of the flights in George’s log. Part of the difference may be that George’s log only reflects ‘air time’, i.e. lift-off to landing, whereas pilot’s time was recorded as engine start to engine shut down. The other possibility is that George was so keen to keep flying on OPS that I wouldn’t put it past him to have deliberately recorded times a couple of hours short on the longer flights.

Click Here To Proceed To Part Three – Liberators