Part 3 – Liberators

Per Ardua Ad Astra

(Through Struggle To The Stars)

Pilot Training | Called To Duty | Liberators | End of Tour | Epilogue

According to George’s log book, we did our first practice flight at Thorney on September 15, 1942 and did our first OPS trip from St. Eval in Cornwall on October 27, 1942, a convoy patrol anti-submarine trip.

After several uneventful trips, on November 1, 1942, while on patrol in the Southwest Atlantic we sighted a convincing looking wake from a U-boat periscope. We depth charged this with great accuracy. It was the practice that a camera started to operate as soon as we opened the bomb doors so that our attacks would be automatically photographed for assessment by the experts when we got back. A few days later, W/C Bartlett had me in to his office to tell me the experts said that what we depth charged was not a periscope wake – but they couldn’t say what it was. We had excellent pictures which showed a perfect straddle of the six depth charges on the wake, and by all analysis experts, a straddle on a visible U-boat wake was a certain ‘kill’.

None of the crew would believe this was not a U-boat, but we couldn’t change the official assessment. There was much muttering about having to ‘bring back the U-boat Captain’s hat’ in order to get credit for a kill. This was also a constant complaint by the Navy anti-sub people.

On November 7, 1942 we were back at St. Eval after a few days in Thorney, and along with two other 59 Libs, we had a briefing for what we were all convinced was a suicide flight. According to the briefing there was a German freighter ‘blockade runner at anchor in the mouth of the Gironde River on the coast of France in the Bay of Biscay about two hundred miles north of the Spanish border and our three aircrew were to “proceed independently but together” and bomb this ship. Our bombs were to be fused for instantaneous explosion whether they hit the ship or the water, and we would have to drop from a minimum altitude of 1500 feet, or we would blow ourselves up. The weather forecast was “ceiling and visibility unlimited” in the target area. There were German fighter bases in a semi-circle around the port area and it was planned that we would arrive there about two hours before dark. Obviously someone in authority had decided it was worth losing our three airplanes and crews for a chance to sink this ship. We were not a happy bunch of aircrew at the prospect ahead of us. We expected it would be our last day alive.

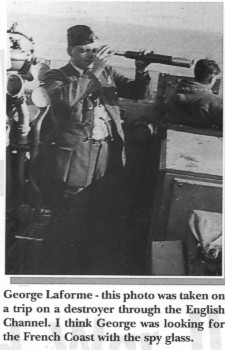

On departing St. Eval we swung wide around Brest and then altered course to parallel the French coast about one hundred miles off shore. Contrary to the weather forecast, about one hundred miles north of the target area we could see ahead a fair build-up of cloud. By this time we had lost sight of the other two aircraft. Visibility deteriorated as we got nearer and, at LaForme’s suggestion, we planned on making a landfall a bit south of the Girande and fly back up to locate the target. Visibility was down to about a mile in rain as we approached the coast at a few hundred feet. We turned north toward the target area; at this point we were below the cloud. As we got closer in we could see the flack going up from what we assumed to be the target and it’s supporting flack ships. As we had to bomb from a minimum of 1500 feet we then climbed to that altitude and were just on top of a low cloud layer. We couldn’t see the target ship but the flack coming up was concentrated enough, we decided our best bet was to fly through the centre of the flack area and bomb on that. This is what I thought we did but LaForme told me a few years ago that we were not satisfied with the first track over the flack – and circled around and did it again this time doing our drop.

The flack was close enough we thought we must have some damage. We cleared the area and headed out to sea and home. The only damage we would find was, when we examined the undercarriage on approaching St. Eval, there appeared to be a piece of metal sticking out just above the left tire that shouldn’t have been there. Thinking the left undercarriage might collapse on landing, we asked St. Eval tower to have a fire truck stand by. The response was that we would have to stand by; they had a lot of take-off traffic and could not risk our blocking their runway. We ended up waiting around for two hours while something like one hundred aircraft took off. We found out the next morning they had been aircraft loaded with paratroopers headed for North Africa, which our troops invaded Vichy France – North Africa that is – all of which was on the news the next day. Our undercarriage did not collapse and we found the other two aircrew from 59 had brought their bombs home because they couldn’t see the target from 1500 feet.

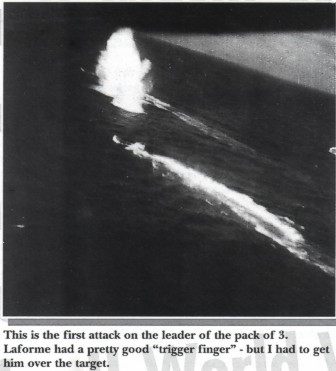

November 10. A few days later we were on anti-sub patrol in the Bay of Biscay patrolling at 5000 feet when we spotted a U-boat on the surface headed north. We were on a southerly heading so it was straight in with bomb doors open. We could see light machine-gun tracer headed our way as we approached but it quit when we were still out of range. We dropped six depth charges when the conning tower was still visible as we dived. George was sure he got a straddle and the photos subsequently confirmed this. We circled and waited for evidence of damage. After about ten minutes, the nose of the U-boat broke the surface and kept coming up at a very steep angle until we estimated it was one-third out of the water. We steep turned around it and the gunners all had the excitement of machine-gunning the exposed portion. We got a lot of hand held camera pictures. After about one half-hour, it slowly slipped back below the surface.

We headed home for St. Eval. This time there was not disappointment at the official result. The Admiralty, which was the authority on damage assessment, gave us a confirmed kill. Apparently the photos showed straddle with the conning tower still visible, and the confirming evidence was the very steep angle at which the U-boat bow surfaced, according to the experts had to upset the batteries which always produced some kind of poison gas. The subject of having killed a bunch of people was never discussed in the crew. These U-boat crews were sinking hundreds of Allied ships and killing thousands of those on board, so as far as I was concerned, the more of them we could kill, the better. I never lost one minute of sleep over it.

We continued doing a series of A/S patrols in the Bay of Biscay and into the Atlantic, interspersed with convoy escorts in the Atlantic, until early December 1942. The 59 Squadron Liberators were taken from us for some other emergency and we returned to Thorney Island to do a conversion on to the B-17, Flying Fortress. We had to wait a few weeks for delivery of the B-17 s and during that period everyone caught up on work that had been neglected due to pressure of operational flying.

The squadron had three odd aircraft. One a Bleinham, a twin engine bomber, a Lysander, a single engine army Co-op aircraft and a Tiger Moth elementary training aircraft – open cockpit. We were encouraged to keep our hand in by flying the aircraft while waiting for the B-17s. I flew the Blenheim one day and scared myself pretty thoroughly. Everything seemed to happen pretty fast. One half hour and I had had enough.

The next day, I took up the Lysander, which was an enclosed cockpit with a very large glass area. I worked up quite a sweat with this one as the sun made it very hot. When I got it down again, I was persuaded to take up the Tiger Moth with our Gunnery Leader Mickey Michelreid. With this open cockpit, my sweat from the Lysander turned into a chill. I wasn’t feeling that well to start with and that night I awoke about two in the morning feeling definitely ill and with a very tight feeling in my chest to the extent that I had trouble breathing. I woke George LaForme, who was my roommate. He took one look at me and went looking for a doctor. Before they got back I had passed out. The doctor slapped an oxygen mask on me and I came to the next morning. I was put into the local civilian hospital where tests were done and it was determined that I had pleurisy. Whatever they did fixed me up and a week later I was released and told to go on leave.

This leave gave Doreen and I the opportunity to get married. LaForme attended as my ‘best man’, and we were married in Cleethorpes on January 7, 1943, following which I was successful in finding an apartment to rent close to Thorney Island and we set up ‘house’.

By the time I returned the B-17 s had arrived and we did our conversion training. The squadron moved to Chivenor, North Devon, to operate from there. We did our first Ops trip, an anti-sub patrol in the Bay of Biscay on February 17, 1943. We did a number of these in the Bay and then on March 9, did a patrol out into the Atlantic. Near the end of our patrol we located a large lifeboat filled with survivors who we could see with binoculars, were pretty far gone. Our ‘green sheets’ indicated one of our own ships was only forty miles south of the lifeboat. We marked the lifeboat location with a couple of smoke floats, located our own ship and, with the Aldis lamp, told them the location of the lifeboat. We saw our ship alter course to go to the lifeboat and then, being critically short of fuel for our return, we headed for home thinking we had done our good deed for the day. A short while later, our WIO intercepted a message from Admiralty to the ship, telling them not to go near the lifeboat as it was suspected to be a trap with a U-boat waiting near the lifeboat. That was the kind of war it was at sea. We never did find out whether the lifeboat people perished or not –but from their appearance, they could not have lived for very long. It was a sad day.

We went back on Bay of Biscay patrols for the rest of February and into March and did our last OPS trip on Fortresses on March 25, 1943. On one of the Fortress OPS trips out of Chivener, we were coming in to land just after dark, when I heard angry voices on the intercom. Just a few seconds before touchdown I got the message that the bottom turret guns had not been retracted. This meant that a landing then would cause a lot of damage to the turret, so I pushed the throttles fully forward, pulled up the wheels and climbed. We then sorted it out. Bart Barton had been last in the turret and the drill was he should have retracted the guns, a pair of .50 calibre M.C.s, during the pre-landing drill. He had not done it, but Al Henry had caught it and he was giving Bart hell for his negligence. After another circuit, and getting confirmation that the guns were retracted, we did a normal approach and landing. As soon as we parked I headed to the back to give someone hell. When I got to there, Al Henry had Bart on the floor giving him a pounding. I decided that Al had looked after the problem and went back to tidy up the cockpit.

We then returned to Thorney to do a reconversion on the state of the art, long range Liberators. I think all crews were glad to go back to Liberators. These were aircraft specially modified for Coastal Command with extra fuel capacity. We could, with careful fuel control, stay in the air for twenty-four hours. We also had the latest in radar, a big help in locating U-boats on the surface and gave the operator a PPI display that one could map read a coastline on. The new aircraft were slow in coming in to get up to squadron strength, so another relaxed period for the aircrews. We got in some air firing and air bombing practice flights. George LaForme got involved in testing some hush-hush low-level bomb sight designed specially for our low level U-boat attacks. George claimed that apart from pilot error, he could drop a bomb within three feet of this target. I claimed he could do that even with the pilot error.

|

|

On May 5, 1943 our crew, that of Pete Wright, Barson and Charlton and another R.A.F. tour crew went to St. Eval on detachment for operations. May 6th was my 21st birthday. The crews were all ‘stood down’ – i.e. released from standby for that night and someone laid on a dinner party in the nearby town of Newquay. As was the custom at that time, the pubs being short of spirits, we took a small supply with us. There was all my crew and four or five of Pete Wright’s crew and the party was just getting going nicely when we collectively ran out of booze. The party was saved by the woman who managed the place. She was an older woman – about forty! – and she thought I should have a really good party so she brought in additional wines and spirits from her reserves in the basement, and the party went on to a late hour. Late enough that there were no buses running back to St. Eval. We split into small groups to try to solve the transport problem. I think it could be said that no one was feeling any pain. I ended up with LaForme, Henry and Thomas and we wandered up the main street being volubly rather derisive about services in England generally and Newquay in particular. Our activities attracted the attention of a member of the local constabulary who approached us with the intention of taking us in hand. AI Henry appointed himself our spokesman and rather belligerently invited the constable to go about his business, that we had been defending his G .d country for a long time and we could do it in our own way and without his help. AI had a brother who was an Inspector in the R. C.M.P. and AI threatened the constable that if he gave us any trouble we’d have the R.C.M.P. deal with him. The verbal war between the two became violent and ended with AI bringing up a good left, resulting in the constable lying very still on the sidewalk. I have no knowledge of events after that until I was awakened in bed at St. Eval at six the next morning with the advice that we were booked to take off at 9 a.m. on an OPS trip.

At briefing we were advised that double patrols were being laid on for escort of the Queen Mary who was westbound for American shores. The shorter range airplanes were escorting until our arrival and we were to escort her through the mid-Atlantic section. I believe they told us Churchill was aboard, but in any event it was a very high priority escort in the south Atlantic. Peter Wright’s crew was to leave at 9 a.m. along with our crew and we were as usual to proceed independently. The other two 59 Squadron aircraft were to depart at 11 a.m.

By the time we were one hour out we knew it was going to be a rough trip weather-wise. There was low cloud with moderate to – at times – severe turbulence. We had to fly below five hundred feet to keep below the cloud. As we progressed it was the normal thing to transfer fuel from the wing tip tanks to the inner tanks. This was our first trip with a flight engineer an eighth man in the crew. One of his duties was this fuel transfer. This clod was transferring from one wing tip at a time, which created severe control problems for the pilots. We finally realized what the problem was and Tommy went back and balanced up the fuel, thus easing up the aileron work. We invited the engineer to find a comfortable spot in the airplane, stay out of the way and not touch anything, otherwise we’d turn Al Henry loose on him. The turbulence continued and got worse – not the nicest thing for a crew that was hung over. LaForme did a wind calculation and it was over one hundred knots – mostly on the nose. He then did a calculation of our E.T.A. on the Queen Mary and announced we would arrive there two hours after dark. The Queen was moving away from us at twenty-four knots, we had a headwind component of ninety knots, and in the reduced airspeed of 150 knots because of the turbulence, this meant we were gaining on the Queen at about thirty-five nautical miles per hour. About this time we got a wireless signal from the Group Control that “the winds are backing and increasing!” I guess they were trying to convey something to us we didn’t know. We came to the conclusion that we should be heading for either Aldergrove or, a better bet, to Gibraltar. While we were still discussing it, a signal came through giving us an immediate diversion to Gibraltar. Now, ‘Gib’ as it was call in the vernacular, was a place you did not approach casually. They were trigger-happy and if an aircraft, any aircraft, failed to give the proper identification, they opened up with the ack ack and shot the aircraft down.

Anticipating we might possibly want to go to Gibraltar, we had been issued the usual sealed envelope with Gibraltar codes. We opened the sealed envelope and it was empty – no codes. This obviously was not our day and we could not go to Gibraltar. A short council of war, as usual, with LaForme, Henry, Thomas and I as Executive Committee, and we decided we’d climb on top of the cloud – at least up into smooth air- and head for Land’s End, the Southwest tip of England and, depending on weather, make a decision as to what airport to try for. We were on top of all cloud at 10,500 feet. George worked out an E.T.A. for Land’s End based on a one hundred-knot tailwind. To cover the possibility of there being stronger tail winds, I decided to descend one hour before the E.T.A. Henry had picked up diversion of other aircraft to Aldergrove, Northern Ireland, so we felt that the weather must be expected to be above landing limits there.

On descent, at about one thousand feet, we broke out of cloud and identified an island near Land’s End. This meant that we had had a ground speed of over three hundred M.P.H., which meant we were in an area of hurricane force winds. We contacted St. Eval- the field was closed – weather. Visibility was good under the cloud over the Irish Sea and we decided to go up to Chivenor, North Devon, where we had operated from with the B-17 s. We were in touch with Chivenor by radio and he was reporting acceptable weather. Then, when we were out only about twenty-five miles, Chevnor called to say that a fog had just rolled in and they were zero-zero in fog. We circled while making another decision. Henry intercepted messages that Aldergrove aircraft were being diverted to Gibraltar. Henry contacted Group on the alternate. They suggested Beaulieu, just west of Portsmouth. We knew Beaulieu; it was almost completely surrounded by balloons and to try to approach through the balloons, in the dark, was something we’d rather not do. These balloons were put up to menace German aircraft if they came below 5,000 feet. These balloons were attached by cables to the ground. An aircraft hitting a cable usually crashed. However, Thorney Island was in the same direction as Beaulieu, so we decided to climb to five thousand feet and try for Thorney. As five thousand feet we were icing pretty badly and it cut off our radio reception as well, so we climbed and finally got on top of cloud and out of it at 12,500 feet.

I should mention that in the modifications to the Liberators they had removed the nose and top turrets, among other things, to reduce weight to carry more fuel and bomb-load, and had removed the entire oxygen system. Now, flying at anything over 10,000 feet, it was accepted that crewmembers might do unusual things, We pass out, get overly aggressive and other unknowns. We discussed this as a crew and that we should watch one another for signs of trouble. I told Tommy that if he saw signs that I was in trouble, he was to take over and get the aircraft down to at least 8000 feet, and I mentioned that if I saw signs of him getting aggressive, I would take the removable hydraulic hand pump which was between the two pilots and thump him on the head. AI Henry was on the radio set just behind the pilots and he told us later that Tommy and I sat there head to head eyeballing each other.

We were navigating blind but hoped to get radio bearings to Thorney when we got closer in. One of the pieces of emergency radio equipment we had was called a DARKIE set. This had a very low powered transmitter and the procedure recommended that when a crew were uncertain of their position (lost), they could call our “DARKIE, DARKIE, PLEASE RESPOND”. Thus the station that responded, and was heard by us, had to be within twenty-five miles of our position. We discussed whether we should declare an emergency

We called Darkie and R.A.F. Boscombe Downs responded. We knew we were within twenty-five miles of Boscombe Downs – LaForme gave me a course alteration and we proceeded easterly. The cloud tops continued to rise and we got up to 16,500 feet – still no oxygen. Eventually, while we were trying to get a radio bearing from Thorney, through a hole in the cloud we could see a set of runway lights. This was good enough for me. I pulled off all power and steep turned in a rapid descent through this hole, got below the cloud about one thousand feet above the ground, found the identifier beacon for this airdrome and found it was a fighter base called Ford.

From there it was only about fifty miles to Thorney Island and, when in range, called the Thorney Island tower for permission to land. The tower said that the field was closed on account of high winds. I informed him that we had declared an emergency a half hour previously so he gave us an OK to land at our own discretion and turned the runway lights on. He was reporting winds of ninety knots with gusts on our approach. We touched down, used almost no runway and parked the airplane on a dispersal point. I think a prayer of thanks went out from all the heathens on board.

A transport picked us up and took us to the OPS room for debriefing. My concern now was for the other crews, particularly for Pete Wright’s, as he had taken off at the same time we had. I went to the OPS controller, found he had no idea what was going on. He didn’t even know any 59 Squadron aircraft were in the air. I told him I thought Pete would try to get into Thorney and if he called in for bearings; to be sure he was given them in plain language. These were usually coded so German intruders couldn’t intercept – but as I told the controller, with the worst storm in twenty years raging outside, German pilots would not be over England tonight. We then went to the Officers Mess for our rum ration and bacon and eggs. Some of the crew had ear troubles because of the rapid descent from 16,500 feet so we got the Squadron doctor out of bed and, besides doing what he could do to help those with ear trouble, he ordered our rum ration doubled.

I was still troubled that the OPS controller wasn’t taking this situation regarding the other crews seriously enough. W/C Bartlett, the Squadron C.O. had his room in the mess building so I went up, got him out of bed, gave him a quick briefing, told him I wasn’t satisfied the OPS Controller was going to do what needed to be done and would he go over to OPS immediately and see if there was anything he could do to help the other crews. Bartlett went to the OPS room immediately, but before he got there Pete’s operator, Rocky Livingston had called in for a bearing and the stupid b…s…d’s had not only sent the bearing in code, they sent it in the WRONG code. The code changed at midnight. OPS coded the bearing in the code in force before midnight, which when Rocky tried to decode it using the after midnight code, it was nothing but garble. This was the last straw for Pete and his crew. They had been in turbulence all day and several hours above 10,000 feet without oxygen. Pete put the aircraft on autopilot on a westerly heading and they all walked out. All survived unhurt. Rocky Livingston landed in water, thought he was in the Irish Sea, inflated his personal dinghy and started to paddle. A minute later he bumped against a wall! He was in a static water tank in Blackpool!

The two aircraft who took off at 11 a.m. didn’t fare well either. The second tour crew were never heard of again. Barsen and Charlton, co-captains of an Australian crew had tried for Aldergrove in Northern Island, but Aldergrove weather closed in and they ended up doing a crash landing on a little private strip on a small island on the Irish Sea side of Ireland. I suspect most of the aircraft is still there.

Thus, of the four aircraft that set out to escort the Queen Mary in the middle of the Atlantic (a completely unnecessary escort with the Queen doing twenty-four knots) we lost three aircraft and eight experienced crewmen. It wasn’t a good start for the #59 Squadron VLR Liberators. Anyway, after briefing Bartlett, I joined the rest of the crew at rum and breakfast. As a crew we got together after lunch. Everyone looked and felt like death. The doctor looked us over and said, “You guys are all grounded until I say you can fly.” Nobody complained.

|

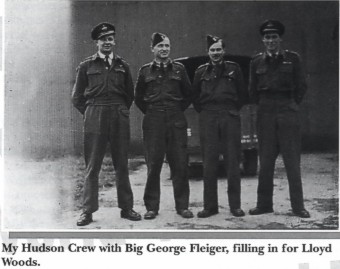

Left to Right: George Laforme, Navigator; Al Henry, WOP/AG; George Flieger, Tailgunner; Ernie Allen, Pilot; Tommy Thomas, Co-Pilot; Lloyd Woods, Gunner; Bart Barton, Gunner |

The next day the rest of the crews, those who had aircraft, left for Aldergrove, where the squadron was to be based indefinitely. An aircraft was left for us and it was a week later that the doctor cleared us as fit to fly. We flew over to St. Eval to pick up our kit that we had left there and then went on to Aldergrove to rejoin the squadron.

Aldergrove was just outside Belfast and at the first opportunity, having heard that the restaurants in Belfast had steak and eggs and all the trimmings, having not seen a steak since we left Canada – this was some treat.

We did a few more practice bombing and air firing flights and then on May 23rd, did another convoy escort, which LaForme’s log book shows at sixteen hours, ‘air time only’. It should be mentioned that until the V.L.R Liberators we put in operation, 59 and 86 squadrons in Ireland and an R.C.A.F. squadron in Newfoundland, there was a six hundred mile gap in the Atlantic in the middle which aircraft from neither side could give convoys coverage, and the U-boats had been having a field day.

On this May 23/43 trip out to mid-Atlantic, we caught up to a Sunderland who was going in our direction. Sunderlands were notoriously slow, and we were feeling sporting, so we lowered our wheels and flaps (so we could fly at his speed) pulled alongside him and flashed him a message on the Aldis lamp, “Put it in second gear!” We got a very rude unprintable response from him, so we pulled up our wheels and flaps, resumed normal speed and left him disappearing behind us.

During the next few months, with our aircraft and a bit of help from the Navy, an end was put to the shipping losses in the North Atlantic. On June 2, 1943, we set out to escort a Northbound convoy in a location a few hundred miles west of Portugal. It was a dawn, or first light escort, and when it was just getting daylight we saw what appeared to be a U-boat just awash, dead ahead. So, ‘bomb doors open’, we roared in and dropped six depth charges. Just too late we realized it was a WHALE. We weren’t the only stupid ones. An Aussie Crew from 59 coming down to relieve us four or five hours later went through the same exercise – ‘bomb doors open’ and dropped another six depth charges on the whale. They had the decency to admit that the whale was already dead. This convoy turned out to be all oil tankers escorted by the American Navy. Shortly after we got on patrol the S.N.O. (Senior Naval Officer) of that convoy called us and asked that we investigate a radar contact he had about forty miles astern. As we had no friendly shipping other than this convoy showing on our Green Sheets, this definitely sounded like action, so we headed out. We soon picked up the radar contact on our set and started homing on it. There was broken air fog in the area. We couldn’t get below it but it was broken enough to verify our altitude above the water, though we had no forward visibility. AI Henry was on the radar and when we were within five miles, we went into the ‘bomb doors open’ routine. As we went below the one-mile on the radar, we were flying about thirty feet above the water, still with no forward visibility, when it suddenly occurred to me that if this was a ship instead of a U-boat, we were going to fly right into the side of it. A little back pressure on the stick and we were on top of this fog bank and there was a damned big freighter just hose-piping tracers at us. Ah – a blockade runner we thought, and there’s the U.S. Navy back there a few miles, so we headed back to the convoy, called the S.N.O. and told him what his radar contact was and that it was UNFRIENDLY. In a very broad southern accent, he said “Well you stay here and look after my chickens and I’ll take a couple of the boys back and look after him”. We stayed until our relief arrived the one that had depth charged our dead whale – then we took off for home. We got the end of the story when we got back to our OPS room. Our ‘blockade runner was one of our own fast freighters, who was over two hundred miles out of position. It took the dullness out of our life for that day – that and the whale!

|

|

|

|

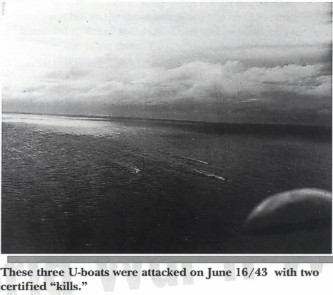

After several more uneventful trips, on June 16, 1943, we set out at 2 a.m. to do an anti-sub sweep down through the Bay of Biscay in a parallel sweep with two other 59 Squadron aircraft. Our aircraft had the inside or easterly of the three tracks. At briefing we were given the story about intense air coverage on the Bay of Biscay both day and night. (Wellingtons equipped with Leigh lights were the night aircraft, but of course in June the hours of darkness were very short.) This intense coverage was resulting in more and more U-boats staying on the surface and fighting it out with the aircraft. By this time all U-boats had a four cannon 88 mm turret mounted behind the conning tower. This weapon was well respected by attacking aircraft. A Sunderland had been shot down the day before in the area we were to patrol.

About 150 miles west of the north-western tip of Spain, again with AI Henry covering the radar and radio set, we picked up a radar contact suspected to be a U-boat. We were flying at 5000 feet above a broken cloud, relying on the radar on the assumption that this U-boat was outbound into the Atlantic, we turned away to the west to manoeuvre so that we would be attacking head on, on our approach. We came busting out of the base of cloud at about one thousand feet and there, a mile and a bit ahead of us was not one, but three, U-boats. We had been briefed that we might find three to five U-boats together on ‘anti-aircraft patrol’ and that if we did, we should circle and call in the other two aircraft for a combined attacked.

I momentarily considered whether to do this, but it appeared we had the element of surprise in favour of our pressing our individual attack so that’s what we did. The three U-boats maintained their VIC formation – until we were in range of their flack, and then turned away so that all three could get their 88’s to bear on us. Soon we had a rattling sound like gravel on a tin roof, it was the ‘shot going through the thin metal skin of our aircraft. We had built up so much speed in our dive, I had to pull the power off to avoid building up too much speed. It was very difficult to control direction at high speed, and needless to say, accurate direction was necessary to track over the U-boat. LaForme would have killed me if I didn’t put us in the right place for him to drop his depth charges. Also, knowing we would want a lot of power after the drop, I had pressed forward the little metal bar that pushed the little electric toggle switches which advanced the propeller pitch. Just as I was doing that there was a yell from Tommy in the co-pilot’s seat – “I’m hit!” By this time we were pretty close to the target and I was ‘busy’. I remember thinking somewhat cynically, “What the hell does he think I can do about it?”

I managed a good track over the leader of the three U-boats and, as soon as we had passed over our target, I called LaForme on the intercom and asked it he thought we had hit the target. (We were barely fifty feet in the air, so I didn’t see how he could miss.) The answer was “Look out the left window and for Christ sake get weaving. I looked out and here was a shower of little mean looking black puffs closing in on us from the left side – I “got weaving”. I had pushed the throttles pretty well wide open on seeing the flack closing in and became aware that we were getting a lot of vibration. I looked at our engine instruments and there was no evidence of the expected increase in power and the tachometers were indicating widely different prop speeds. I asked for and got a course to the nearest land in expectation we would not long remain airborne.

I had swung into a left turn as soon as we were out of range of those two remaining U-boats. For some reason I couldn’t figure out, given the engine power the instruments were indicating we were staying in the air with a reasonable airspeed on the gauge. We still had six depth charges on board. Tommy seemed to have had a miraculous recovery from being hit. It turned out a shell had gone through the A C. junction box, distorting it’s shape which flung its cover off and it was this cover that had hit Tommy.

About this time somebody shouted that one of the U-boats was diving so we turned in to drop our remaining depth charges on it. The gen was that to get a ‘kill’ on a diving U-boat, the depth charges had to be dropped within thirty seconds of the conning tower going under. It was looking like we’d be late on that timing when we noticed the third one had started to dive, so we switched our attack to it. We had no trouble dropping our depth charges within the thirty seconds and George reported a good drop.

There was a lot to think about for a few moments. I sorted out the engine vibration; the engine pitch was all out of synchronization. The engine instruments were not indicating it because they worked on A C. power and the hit on the junction box at Tommy’s elbow had put that out of action. Should we circle and attempt to call in the other aircraft? We reviewed the signals that AI had transmitted which were as follows:

- Time – attack time – two minutes

message – attacking U-boat. - Attack time + one minute

message – S.O.S. - Attack time + three minutes

message – attacking U-boat - Attack time + four minutes

message – attacking U-boat

|

|

We knew the other crews would have monitored our transmissions and our position had gone with each message, so they were in a position to make their own decisions and as we were well within range of the Ju88 fighters on the French coast, who could ‘home’ on to us if we made lengthy transmissions so that was voted down. I didn’t have any trouble getting a crew consensus that we should get up into the layer of cloud above us and stay in it till we were long past Brest as we headed for Aldergrove, with the option of going into St. Eval on the way if we found aircraft damage to justify it. No serious damage was found. A shell had cut the actuating rod for the bomb doors just behind the navigator’s position, and we had to wind the bomb doors manually – no big deal. This and losing our A.C. power was the most serious damage we had. The ground crew counted 192 holes in the aircraft when we got back, but apart from the cover of the A.C. junction box there was no serious damage.

The Operation Controller was quite critical of our decision to not call in the other two aircraft and to make the attacks ourselves. We defended our decisions and told the Controller that if he wanted to make the tough decisions held better be on the aircraft. The good news came the next morning, a signal from Coastal Headquarters congratulating the squadron and the crew. We had been given a ‘kill’ assessment on the first U-boat attacked and a probable kill on the second one. The crew had an evening out in Belfast to celebrate.

I think it was before the above mentioned trip that LaForme, Henry and I had been instructed to attend at Coastal Command Headquarters for an investigation of the loss of the three 59 Squadron Liberators on May 7, 1943. The investigation was conducted by Air Marshal Slessor, head of R.A.F. Coastal Command. Pete Wright, his navigator and W/OP also attended. Slessor interviewed us each separately several times. In my interviews he started (with a shorthand artist taking notes) from our briefing prior to the trip all through until and ending on my having got W/C Bartlett up with the request that he go to the OPS room to see if he could help. I had been quite bitter about the Controller at Thorney Island screwing up on the signals handling of Pete Wright’s aircraft. We were there five days, Monday to Friday. On my last interview he took the time to tell me some the results (1) that Controller at Thorney Island was disciplined and reduced in rank from S/Ldr to PIO and moved to a non-operational station and (2) up until this time an aircraft on operations was monitored only by the Group that the aircraft took off from. For clarification, the whole of the U.K. for Coastal Command was divided into four groups, South-west, North-west, South-east and South-west The new policy he instigated as a result of this investigation was that all aircraft with a P.L.E prudent Limit of endurance of twelve hours or more would be monitored by all four groups, which basically meant all signals to and from such aircraft would be recorded by all four groups. It was so sensible, we wondered why it had not been done months before. Slessor also said that a report had to go to Churchill. Slessor went on some time later to the top appointment, “‘Marshall of the Royal Air Force”, so when I met John Curtiss in 1969 or 1970, whenever it was it meant that I had met and chatted with two officers who reached the # 1 position in the Royal Air Force!

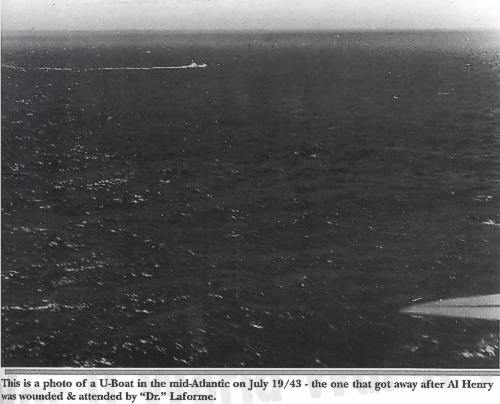

On June 21, 1943, on another convoy escort, we sighted another two U-boats, but they dived well before we could get in an attack. We did a number of AIS patrols and convoy escorts and a fair number of air practice flights until July 19, 1943, when we got “some more excitement”. This fight an Anti-sub patrol straight west from Aldergrove into mid-Atlantic. By this time our bomb load had been changed from twelve depth charges to six depth charges and two “homing torpedoes’. These homing torpedoes, when dropped reasonably near a U-boat or ship for that matter, would ‘home” acoustically on engine sound and detonate on contact. This was a “secret weapon” and we had been briefed that these torpedoes could not be dropped on a surfaced U-boat, the reason being that there were problems with them, in that sometimes when dropped, something malfunctioned and the thing would just run in ever decreasing circles until it stopped and the information was it the Germans captured one or them, they would quickly figure out how to neutralize against the homing feature of the weapon and it would become useless. We were briefed that any Captain who dropped one of these on a surfaced U-boat would be Court Martialled. Also, any aircrew found to have discussed this weapon other than with his own crew would be Court Martialled.

Back to this flight. At almost the westerly limit of our patrol, we located a U-boat on the surface and started in on an attack “depth charge”. At extreme range we were hit on the leading edge of the left wing, so, thinking discretion would be the better part of valour, we broke off the attack, expecting we would persuade him to dive and then we would get him with a homing torpedo. We tried every trick in the book to get him to dive, but no dice. He stayed on top. After about an hour of playing games, we were running out of time – our fuel required we leave soon or run out before we got home. We decided we would have to attack with our depth charges. Knowing the effectiveness of the four cannon turret behind the conning tower, we tried to manoeuvre to get an attack in from the bow. He manoeuvred to prevent this. Our final tactic was to go into a steep turn around him trying to get ahead of his conning tower. We tried left and right turns – he could turn direction and turn faster than we could.

Tommy Thomas had by the date of this flight, gone on a Captain’s course and his replacement was a very shy little English Sergeant pilot. At one point we were close in on a right hand circle and the flack was coming pretty close. Al Henry was on the beam gun trying to shoot their gunners and this second pilot had the big F-24 camera up trying to take pictures. I was getting pretty frustrated by this time and I snarled at him to get rid of the camera and tell me what was going on, on the deck of the U-boat. We ended up in a left-hand turn and by getting in close we were moving up toward the front of his conning tower. We were taking a lot of flack and I could see AI was knocking down some of the people on the deck of the U-boat. There came a time when I figured I could level out and bomb across ahead of the conning tower. As soon as I committed to this, he must have thrown both engines into reverse and we tracked across in front of him. I thought, my God, we are going to have to do this again. Then somebody called that the depth charges had gone off ahead of the U-boat. It turned out that LaForme had figured we were going to splash and had released the depth charges as we crossed in front of the U-boat. We pulled away and someone called that Henry was hit and they needed bandages and morphine. LaForme was the nearest thing we had to a medic and he went back and did a first class job. We set course for home with Henry having enough morphine in him to kill all pain.

We had no nose gun. Crews had been bitching for them for months. The engineering had been done but someone had decided they would only install the guns as the aircraft came in for routine overhaul inspection. It was something over six hours back to Aldergrove. By the time we arrived I was really steamed up about not having a nose gun. We had radioed in that we had wounded on board, so there was a reception committee on arrival. #59 had a new C.O by this time, a W/C Gilchrist. The ambulance people took AI to the hospital. Gilchrist and the Station Group Captain asked me to ride back to OPS with them. During this ride, I really exploded about the stupidity of not having the nose guns installed. They were quite tolerant of my outburst and when I went to breakfast the next morning, found that orders had gone out for both 59 and 86 Squadrons that no OPS were to be done by the Liberators until the nose guns were installed. Somehow I felt better, but AI had a bad knee for the rest of his life and he was gone from the crew.

Before we did another trip, LaForme was the only one left of the original crew. Woods and Fleiger went on rest. Barton went to a Canadian Flying Boat Squadron. Tommy had already gone on his Captain’s course. LaForme and I went on leave and come back to start our to train a new crew – an Englishmen. The fun had gone out of the Squadron. By this time all of the North Coates crowd had gone on rest.

It should be mentioned that somewhere shortly after the June 16 trip, someone came to my room and told me I was to report to the Station Commander immediately. I thought, my God, what have I done now to be on the carpet in front of the station Group Captain. Needless to say, I went. It turned out it was the Group Captain’s pleasure to tell me that I had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The Citation was the usual blarney about setting a high standard for the Squadron and pushing attacks against the enemy over and above the call of duty. He congratulated me but confirmed that he hoped I would not take this to be a signal that I should ease up. I felt that it should have been a Citation for the whole crew, but the R.A.F. didn’t do things that way.

A few weeks earlier the Group Captain had taken an anti-sub patrol in the Bay of Biscay with our crew. It made us all very nervous having him on board but we got through the trip. At one point AI Henry picked up a radar contact which we treated as a U-boat contact and ‘homed’ in on it with bomb doors open. He stood up between and behind the pilots on the run in. Visibility was very poor. It turned out the contact was on some boards fastened together floating, and he was very impressed that our radar could pick this up.

On the date of July 1st, George’s logbook shows me as being a Flight Lieutenant, so I guess I was promoted somewhere around that time.

The last OPS trip with me in George’s logbook was October 24, 1943 and I was grounded after that trip. I hadn’t been feeling well for some time. The squadron had moved in early September to Ballykelly, up North in Ireland and on coming in to land after dark, it seems I levelled out feeling for the ground a couple of hundred feet in the air. LaForme was standing behind and he roared at me “Ernie go round again”. I pushed open the throttles and climbed, then turned to George and asked what that was all about. He said I had been trying to land two hundred feet above the runway. This was the second time, as it had happened a couple of trips earlier. George had to report it to the C.O. and he grounded me – end of tour.