Ernest E. Allen

Per Ardua Ad Astra

(Through Struggle To The Stars)

Prologue

World War II, Liberator pilot, Ernest Allen details herein his memoirs of service on the coastal command in the 59th Squadron for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in conjunction with the Royal Air Force (RAF). For his achievement, Ernie Allen was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. In post-war years, E. Allen went on to become a successful land developer including founding the Seaway Mall in Welland Ontario Canada. We invite you to read this fascinating account and to drop a line to the author’s son at: mike4761@gmail.com

Table of Contents

Pilot Training | Called To Duty | Liberators | End of Tour | Epilogue

Part One – Pilot Training

This history of my R.C.A.F. years as a pilot is being written at the request of my son Michael, who, I suggest, asked me to write it in hopes that I would then not feel the urge to tell him line-shooting stories about my war-time experiences.

Since my targeted readers are mostly of the generations that were either infants during the 1939-45 war or were born since, I feel some background is justified.

I turned 17 on May 6, 1939, so I have a good memory of what was and still is called the Great Depression, but having been fortunate enough to have been born on a farm, food was never a problem, but clothing sometimes was.

During the years 1935 to 1939, there were constant articles in the newspapers of the likelihood of war in Europe with Germany making repeated aggressive moves against neighbouring countries. Against that background I found it difficult to decide what occupation to try for as a lifetime career. I finished four years of high school in June 1939, with my Dad pushing me to go on and qualify as a teacher. This had no appeal for me, and two events attracted my attention to flying. One was the almost daily flights of Harvard training planes from Camp Borden over our area. The second was that in May of 1939, my Dad paid for me to have a trip as a passenger in one of the private planes at Brantford Airport. During this ride, the pilot permitted me to take the controls for a while and coached me as to how the control the airplane, and what to do with both the foot and hand controls. This fired my enthusiasm for becoming a pilot and I felt that the coming war would give me a chance at this.

Germany invaded Poland at the end of August 1939, and a few days later, Canada, following England’s lead, declared war on Germany.

Canada’s Army and Navy went into action, but the Air Force was my interest, and the R.C.A.F. was chosen by the allies to operate what was termed the Empire Air Training Plan. Hundreds of airdromes were built for training of pilots, observers (navigators), wireless operators and air gunners.

R.C.A.F. recruiting offices were set up in major cities, including Hamilton.

Although I would not reach the minimum age for enlistment (eighteen), until May of 1940, I went down to Hamilton in February 1940 to “get my name on the list”. The recruiting officer told me that I could apply but could not be called until I turned eighteen. Part of the enlistment application was to fill out a medical history and have a medical examination. In the medical history I showed rheumatic fever as one of my previous illnesses. When the doctor saw that, he said sorry, a past history of rheumatic fever was a no-no for any aircrew and he would not be able to approve my application. After some discussion, in which I pointed out that the rheumatic fever diagnosis was by a country doctor and that I had only been out of school for one week, the doctor solved the problem by telling me to fill out another medical form and make no mention of the rheumatic fever. On this basis I passed the medical and went on the waiting list.

In late July, a buddy of mine, Don Hammond, went to London, Ontario recruiting office and applied for aircrew enlistment, and he was called the next week. This made me think of my making an application in London and when the harvest was finished, in mid-August, I went down to Hamilton recruiting office, and asked for my papers so that I could try London. After some discussion, the recruiting officer said if I would leave my papers with him, he would guarantee I would be called within a week. His word was good.

Part of my reason for hurrying up the enlistment was that the Battle of Britain was not going well at that time and I was afraid the war would be over before I got in. I was signed in on August 20, 1940 and proceeded immediately to Manning Depot, which was in the old Horse Palace at the Canadian National Exhibition grounds in Toronto. The routine at the Manning Depot was to get us (a) into a uniform that came near to fitting. Many of us had to go to a private tailor to get an acceptable fit. (b) Get vaccinations. (c) Parade grounds marching etc.

About the fourth morning, I overslept and in rushing to get cleaned up ready for parade, I overdid it, and fainted at the wash basin. The Corporal insisted I go on medical parade. When I got to see the doctor, he asked a number of medical questions, and when very pointedly asked if I drank very much. I replied just as pointedly that “I have never had a drink in my life!” He appeared to be amused at this and closed the discussion by suggesting that a beer or two once in a while would improve my circulation. Two beers that evening had a very relaxing effect on me.

On Sept. 10, I was sent by train with about thirty others to Camp Borden, an R.C.A.F. base just north-west of Barrie, Ontario. We were detailed there for guard duty. As air crew in waiting our dress required that we wear a white “flash” in our hats. See photo. Typical guard duty was in a guard hut out on the edge of the airfield. After the first few nights we stopped expecting Germans to attack the airfield and looked for something to relieve the boredom.

Camp Borden was a single engine pilot training school – Harvards. We white-flashed guards were given permission to fly as passengers on training flights. One nice day, another chap and I went up to the flight office and got permission to go up for a ride with pilots doing practice flights. I had an enjoyable flight – the other guy and his pilot were killed when the pilot failed to recover from an inverted spin. Such was fate.

Many of the guard posts were out at the edge of the field with scrub growth for another hundred yards before the bush proper started. In this area, deer used to wander around, with just the eyes visible at night. One night at a guard shift change, at 2 a.m., the four of us decided we should challenge this activity, and after shouting “Halt – who goes there?” with no response, we all fired a shot at the deer (plural). The deer took no notice but the Sergeant of the guard arrived very quickly and was somewhat verbally abusive to us, and arranged for us to be paraded before the station commander officer the next morning. The C.O. had a good sense of humour. After telling us that we could be court martialled for what we had done, he relaxed and told us that since our whole group was being posted the next day to Toronto to #1, Initial Training School, he would just forget the incident.

The Initial Training School, informally called the I.T.S. was located in the old Toronto Hunt Club, and was basically a “ground school” where some clever people decided whether each one of us should go off to (a) pilot training, (b) air observer training or (c) wireless operator-air gunner training or (d) straight air gunner training.

Most of the several hundred of us in the class wanted to be pilots and there were all sorts of stories went round as to how and on what the choice would be made.

There was some truth, as it turned out that the brightest and highest educated would be selected as observers as that required the greatest skill in mathematics. Over half of the class had several years of university behind them, so with my four years of high school (junior matriculation certificate), I was not likely to be chosen as a navigator. Like most of the class I decided to work like hell and hope for the best. It was be general agreement, the most intensive schooling most of us had ever had. It lasted only two weeks, but if it had been much longer there would have been many of us with health breakdowns. On the second Friday night we were all given forty-eight hour passes and told to report in Monday morning and we’d find out what was in our future.

I hitch-hiked home to St. George – a two hour drive and as luck would have it I got a ride all the way with a chap who had been a pilot in the first world war, 1914-1918. I told him I expected to start pilot training the next week, and until we arrived in St. George, (in fact he drove me home to the farm), he proceeded to give me a lot of advice about how to survive in combat. His advice was still good advice, as I later found out.

I enjoyed the two days at home and told the family not to be surprised if I ended up as an air gunner instead of a pilot.

On returning to Toronto on Sunday night, all of our postings were on the bulletin board and I found my name with about twenty others on a posting to the Elementary Flying Training School at Windsor Mills, Quebec, for pilot training. I was so happy, I cried.

A lot of the others had come back on Sunday evening as well and a bunch of us who were posted to Windsor Mills found each other and celebrated with a few beers – a traditional way of celebrating good or bad news.

On Monday morning we Windsor Mills pilots were given our travel documents including first class tickets on a train for Windsor Mills.

This was early November 1940, very much winter in Windsor Mills, Quebec (see photo) and the aircraft, all Fleet Finches, were ski-equipped – no wheels.

After a few days of ground school, we were finally each assigned to an instructor – each of which had four student pilots to start with and we started getting actually instructed on flying an aircraft. This was exciting stuff.

My instructor was an old fellow – about twenty-eight years of age, by the name of Alfie Cockle. Our temperaments were suited and we progressed without much pain – about two-hour instruction in the air each day, with the rest of the day in ground school.

It wasn’t long before it became obvious that some of the students were disappearing and we soon found out why. They were “washed out”; i.e. failed as possible pilots. One third of our class were “washed out” before ever being allowed to go solo. Eight to ten hours dual was the time in which we were expected to be sent solo. At about the nine hour mark, I was getting concerned and then Alfie quietly asked me to park over at the flight office and let him out and go off on my own. I was to just do a take-off, circuit the field and land and bring the aircraft to the flight office. I managed to do that without attracting too much attention – and pull the power off and touch down. There were ground crews there to help get the aircraft back to the parking area.

Two incidents stand out in my memory about flying at Windsor Mills.

- One day, with a very strong wind blowing Alfie and I took off and it wasn’t very long before I noticed we were backing away from the airport because of the strong wind. On my mentioning this to Alfie he cautioned me not to make a turn or we would never get back to the field. The procedure was to back away until downwind from the field and then stick the nose down and power down at a fast enough speed to gain on the field again and when half way down the field, pull into a 360 degree turn, and line up over the middle of the field and allowing suitably for the wind, keep on enough power to land on the field close to the flight office.

- Again on a dual flight with Alfie we were out to do a little emergency landing practice when at about 1500 feet above the ground, the engine quit completely – caused by carburator ice as it turned out. I said “Over to you Alfie”. He said “Hell no it’s yours. Find a safe place to put it down.” I looked around for a suitable field. There were not many choices, but I picked one I thought we could make and headed for it. Of course there was a fence at the approach end of the field. It was touch and go as to whether we would clear the fence but we did and landed in about two feet of soft snow. We got out and Alfie pointed to a farm house two miles away and instructed me to go to the farmhouse and phone our airfield to send ground transport to pick us up. There was two feet of soft snow and it was not an easy walk – but at eighteen you can lick the world.

The ground school here was a mixture of theory of flight, armament, navigation and weather study. Our flying was of about fifty hours total flying time.

Just before Christmas 1940, those of us who didn’t fail the course were posted for our next stage of training to a Service Flying Training School, S.F.T.S. About a half dozen of us, including myself, were posted to #8 S.F.T.S. at Moncton, N.B, with train transportation laid on. We were each given our personal service documents in a sealed envelope to take with us to Moncton. We were all very curious as to what was in the envelopes, and finally made a pact that we would all open our envelopes and see what our Windsor Mills instructors really thought of us. Alfie Cockle’s only comment on my flying ability was “a bit rough but should make a good bomber pilot”.

On the evening of Dec. 24, 1940, we stopped for something at Riviere duLoup – across the river from Quebec City. No one seemed to be able to tell us how long we’d be there and after going to the washroom, I came out and the train had left. Not wishing to be charged with desertion, I reported to the R.C.A.F. Service Police in the station and told them of my problem. They were very helpful. They gave me a bed in their holding cell, but left the door unlocked. They said there would be a Moncton train along about ten o’clock the next morning and arranged a ticket for me on that train. That next morning being Christmas Day and the first time I had been away from home at Christmas, I was feeling very lonely, but felt much better after phoning home and talking to several family members. It was the most lonely I ever felt throughout my five years in the Air Force.

I arrived in Moncton in mid afternoon. #8 S.F.T.S. was a real mess, mud everywhere except the paved runways. We were the first course of pilots at the school, so it was a bit disorganized. Construction was still going on everywhere except on the runways. The aircraft we were to train on were Avro Ansons – twin-engined.

Our O.C. flying was Wing Commander Hodgson, an ex Mountie. One of the instructors was an ex Rum Runner. He and Hodgson had had previous experience before the war, but Hodgson had never caught him. On the first parade Hodgson discovered him and his first words were “I’ve finally got you! However, he took no action, but stories of their old escapades were all over the station for a few days.

The training here, both flying and ground school, was very demanding. We were scheduled to get our wings about the middle of March 1941. However, about a week before the schedule wings parade, I came down with Scarlet Fever and was put in Moncton General Hospital in isolation for six weeks and missed the graduation. I was put into the third course for final training and got my wings in early June. I was made a Sergeant and we were all to be given two week leave. Before leave I was on Dental Parade one morning and while there, there was a call for volunteers to go to Charlottetown for a General Reconnaissance course which meant one would go to R.A.F. Coastal Command. A buddy of mine put my name in as well as his own – probably one reason I survived the war.

While I was home on leave a telegram arrived advising that I had received a commission as a pilot officer, and that I should get an officers uniform before going to Charlottetown. The family & I were all very proud that I had received a commission. About Sixty percent of the pilots on our wings course were made officers, the rest were sergeant pilots.

I reported to Charlottetown toward the end of June, in time to start their course of training. The course was mostly navigation. The concept was that when we crewed up for squadron, there would be two pilots who would alternate as pilot and navigator, there would also be a wireless operator and a gunner. As will be seen, this policy would be changed before we got to a squadron, where the crew would be one pilot, one navigator and two or more wireless operator-air gunners, depending on the aircraft.

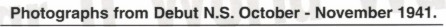

On the course were Jack Gordon, Can Barnett, Roy Neilson and myself, which foursome would be together for about a year – and Roy Neilson and I ended up on the same squadron for another two years. There were about twenty pilots all together on the course. The instructors were all R.A.F. tour expired pilots “on rest” and were the best lineshooters I ever ran into.

Of about twenty pilots on the course, at the end of August we were all posted to an operational training unit at Debert, N.S. for training on Lockheed Hudsons, with the intention that we would crew up there and each qualify as Captain for Atlantic ferrying – take one aircraft over to England – stay there and go to a squadron after some more training.

We were the first course of pilots for training at Debert. The instructors were mostly pilots who had done an operational tour in England on Avro Ansons. Most of them were frightened of the flying characteristics of the Hudsons. On average they gave us three hours of dual instruction and then sent us off solo. In late October a flight commander authorized cross-country lights for early morning. He put the authorization in the authorization book the night before. The field was fogged in, in the morning but no one turned up to cancel the authorization so as a group we decided it must be intended that we go ahead and take off. The instructors had been giving us the line that there would be a lot of bad weather flying when we got to England, so this must be part of the training.

I was the third airplane in line for take-off. I taxied out to the middle of the runway, couldn’t see either side of the runway in the fog, so I moved back close to the left side of the runway and was able to keep straight on the take-off run by watching the line between grass and asphalt. One aircraft crashed on take-off. Another almost hit the control tower, which caused a bit of excitement there. The weather cleared up for our return, as expected, some five hours later. The instructors were severely criticized for not getting up in the morning to make the decision for us as to whether the weather was fit for flying.

In early November a cross-country flight from Debert N.S. to Windsor Ontario was laid on for twelve aircraft. The plan was that we would all do a night full-load take-off – a frightening experience for even experienced pilots. The afternoon before we were all required to “air test” our aircraft. I found the compass was out by thirty degrees on a westerly heading and asked the Flight Commander for change of aircraft. He implied that I was “chicken” so I agreed to take the aircraft on the basis that if I couldn’t maintain visual contact with the ground I would turn around and come back.

My roommate Beech O’Hanley was the first aircraft to take on just after 1 a.m. He climbed to about 2000 feet and then something went wrong and the aircraft turned upside down and went straight into the ground – “all killed”. The rest of us were held for a daylight take-off. For my flight the weather held OK until we were about fifty miles west of Montreal, then came rain and lower and lower cloud. We stayed visual, but with very little forward visibility, with our Radio Direction Finder compass tuned in to St. Hubert. Little did we know that this transmitter had been moved a week earlier to Dorval – a little further east.

We had information that Dorval Airport was open and an operating airport, as Montreal’s main civil airport but we had no information on their radio operating frequencies. A look at our map indicated that the best way of getting to Dorval in poor visibility was to coast crawl around the island. This took us via the St. Lawrence River through downtown Montreal, where the river gets pretty narrow. At one point we were favouring the right side of the river, and on looking up ahead, we were about to run right into the Sun Life building about half way up. A quick turn put us out on the river again. The next thing there was a bridge ahead and above us. The sensible thing to do was to fly under it, but all of our training re bridges was to not fly under them. So, as we approached the bridge, I pulled back on the control column, climbed to 400 feet, which would clear the bridge but put us into the cloud – on instruments. I counted to thirty and then eased the control forward and broke out contact over the river on the other side of the bridge, and continued around the island to a point the map indicated that a southerly heading would put us over Dorval Airport. We had no radio contact with the tower, but they got the idea we wanted to land and gave us a green on the lamp and we did a timed runway procedure to bring us around lined up on the runway in use and we went in and landed. By this time the wireless operator had found a channel on the radio that we could talk to them. They instructed us to park in front of the tower and await instructions.

Conversation on the radio indicated that the commercial airlines were being diverted elsewhere because of us and other Debert aircraft, most of who were trying to land at Dorval without radio control. We had just nicely got sorted out at our parking place when a Group Captain came out and angrily ordered us to take off out of there. I immediately told him we would not do that, as our pilot’s compass was unserviceable. He stomped off and left us alone.

All but two of the Debert aircraft either came into Dorval or tried to two of them crash-landed while trying. A message was given to us ordering us to stay at Dorval until someone came up from Debert to decide what should be done to stop us from killing ourselves. By this time three of the aircraft and crews had been wiped out and a fourth crew had safely landed in the bush, three hundred miles east of Montreal.

We, the surviving Debert crews, all checked in at the Mount Royal Hotel in downtown Montreal and enjoyed ourselves for three days waiting for the weather to improve and for further instructions. They eventually sent a bunch of instructors up from Debert to fly back to Debert with us, and after the partying we had been doing in Montreal it was probably a good idea. Needless to say I had the compass “swung” before our departure from Dorval.

We had a bit more training at Debert and then orders came in that all the surviving crews from Debert were to be posted to R.A.F. Ferry Command, Dorval Airport in Montreal, where we would get final training for Atlantic Ferrying on Hudson aircraft.

The night before we were to catch the train for Montreal, there was a course graduation party in the Officers’ Mess. The party included the non-commissioned officers on the course. This was something very rarely done in the service a party in the Officers’ Mess that included the sergeants; and this one was further evidence that it should never be done.

After many drinks it was discovered that someone had peed in the Group Captain’s hat – enough to fill it. Obviously more than one person. The Group Captain was very upset and ordered that we would not leave for Montreal until the guilty people confessed. Nobody confessed, and after four days, Eastern Air Command of the R.C.A.F. ordered the Group Captain to release us to go to Montreal. This was mid-November of 1941.

The plan was that each crew, after getting checked out by the instructors in Ferry Command, would deliver a Hudson to England, Hudson’s that were being supplied by the Americans for the R.A.F. This would save a lot of money being paid to the civilian pilots who had been hired by the R.A.F. to deliver airplanes to England from Montreal at $1000 per trip. Nobody asked us if we could do it, but very few of us thought we would be successful in getting a plane across the Atlantic to England, especially in winter weather. We did some more training at Dorval and, during the first week of December, got our logbooks endorsed as “Qualified as Captain for Atlantic Ferrying”.

A few days later, December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbour was all the news. This brought the U.S.A. into the war.

Click Here To Proceed To Part Two – Called To Duty